The health risks of a sedentary lifestyle affect billions worldwide, with global estimates showing one in three adults and 81% of adolescents fail to maintain enough physical activity. This is not a local issue but a global one. Physical inactivity has become the fourth leading cause of death globally, leading to 3.2 million deaths each year.

Since 2010, the number of inactive adults has grown significantly, now affecting 1.8 billion people worldwide. Scientists predict that by 2030, more than one-third of all adults will not meet basic activity recommendations, Typically including at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per week, along with muscle-strengthening activities on two or more days a week.

Women are less active than men worldwide due to cultural values, reduced access to exercise opportunities, and increasing use of technology for work and daily tasks. The health risks of a sedentary lifestyle affect women more as data shows, creating a concerning gender gap in physical well-being.

The cost to society is staggering. Without changes in activity levels, nearly 500 million new cases of preventable diseases will develop globally by 2030. These illnesses will burden healthcare systems with approximately £240 billion in costs, underscoring the urgent need for increased physical activity.

This post examines how inactive living changes your body, damages long-term health, and affects daily life. Using insights from worldwide research, we’ll share evidence showing why movement matters and practical ways to become more active, empowering you to take control of your health. For instance, taking regular breaks from sitting, incorporating short walks into your daily routine, or engaging in activities you enjoy can all contribute to a more active lifestyle.

Mortality Risks Associated with Sedentary Behaviour

90%

49%

17%

13%

The Health Risks of a Sedentary Lifestyle Today

The World Health Organization reports that physically inactive people are 20% to 30% more likely to die earlier than those who stay active enough. This higher death risk affects various aspects of health throughout the body, including your own.

A study of over 700,000 people found shocking results – people who stay inactive are 49% more likely to die from any cause and 90% more likely to die from heart problems. Every extra two hours spent looking at screens raises the risk of heart disease by 17%. These numbers clearly show how lack of movement harms our health.

Lack of activity damages more than just the heart. When people don’t move enough, their bones lose strength quickly because the body begins breaking down bone tissue faster. The body’s ability to process energy and use food properly (metabolism, the process by which your body converts what you eat and drink into energy) also rapidly declines with reduced movement.

Different groups face different challenges with staying active. People over 60 tend to become less active. Young people also struggle – 85% of teenage girls and 78% of adolescent boys don’t move enough to meet basic health guidelines. The health risks of a sedentary lifestyle hit certain groups harder than others – particularly older adults and people with disabilities.

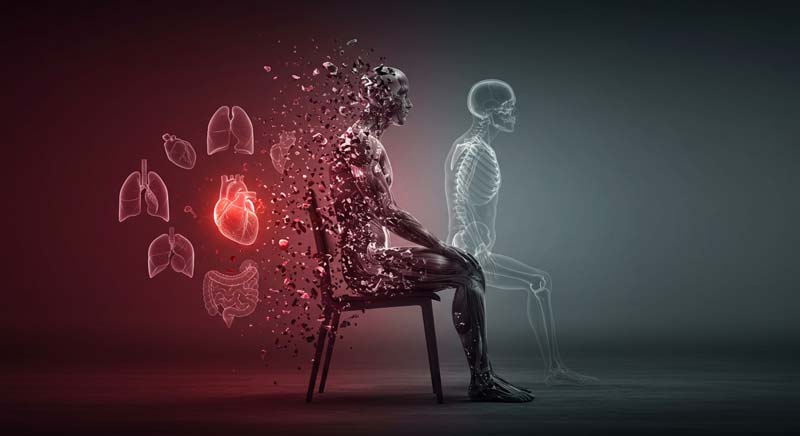

Physical Changes from Prolonged Inactivity

When regular movement stops, the body begins a series of rapid changes that affect overall health. These alterations start within days of becoming inactive as the body quickly adapts to reduced physical demands. The changes are particularly noticeable in muscle tissue, including the heart, where health risks of a sedentary lifestyle become evident through measurable physical decline.

Scientists have observed that short periods without regular activity can trigger significant bodily changes. These modifications affect everything from how healthy muscles work to how the body processes food for energy. The impact of these changes creates health risks of a sedentary lifestyle that can last long after returning to activity.

Research has identified several key physical changes that occur when movement decreases. These alterations affect multiple body systems simultaneously, creating a torrent of physical adjustments:

Body Composition Changes:

- Muscle Mass Reduction: Muscles begin weakening within days of inactivity, leading to noticeable strength loss

- Bone Density Decrease: Bones start losing minerals rapidly, becoming more fragile and susceptible to breaks

- Fat Distribution: The body stores more fat, particularly around internal organs

Energy System Changes:

- Reduced Oxygen Processing: The heart and lungs become less efficient at delivering oxygen throughout the body

- Decreased Energy Production: Cells become less effective at creating energy from food

- Blood Sugar Control: The body’s ability to regulate blood sugar levels diminishes

Movement and Balance Changes:

- Joint Stiffness: Reduced movement leads to less flexible joints and increased discomfort

- Balance Difficulties: The body’s ability to maintain stability declines

- Coordination Problems: Regular movements become less smooth and require more effort

These physical changes can create a foundation for more serious health issues that can develop over time. The body’s extraordinary ability to adapt works both ways—it can decline with inactivity just as it can improve with movement.

How a Sedentary Lifestyle Impacts Your Health Risks

The human body thrives on movement. Yet modern life often keeps us still for hours, leading to significant health challenges. Research shows that prolonged inactivity increases the likelihood of developing several severe health conditions.

Through extensive studies involving hundreds of thousands of people, researchers have uncovered clear patterns of how the health risks of a sedentary lifestyle affect our bodies. A striking finding shows that people who sit for extended periods face nearly double the risk of heart-related problems.

Time Matters: The Impact of Daily Inactivity

Living with limited movement throughout the day creates measurable changes in health risks. For instance, each additional hour spent sitting increases the chances of developing diabetes. The effects become more pronounced when inactive periods stretch beyond four hours without breaks.

Cancer and Organ Health

Physical inactivity influences cancer risk in several ways. Studies have found that health risks of a sedentary lifestyle include increased chances of developing certain cancers, particularly those affecting the colon and breast. The risk rises between 8% and 28%, depending on the type of cancer.

Silent Changes in Brain Function

The brain requires regular movement to maintain optimal function. When activity levels drop, cognitive performance can decline. This affects memory, mood, and overall mental sharpness. Additionally, the risk of developing conditions like depression and anxiety increases by 28-32% in people who remain inactive.

Heart and Blood Vessel Effects

A lack of movement significantly affects the cardiovascular system. Blood vessels become less flexible, and blood pressure often rises. Even small increases in blood pressure—just 20 points in systolic or 10 in diastolic pressure—can double the risk of developing heart disease.

Metabolism and Weight Control

The body’s ability to process nutrients changes dramatically with inactivity. This affects everything from blood sugar control to how efficiently the body burns calories. These changes can trigger a cycle where weight gain leads to further inactivity.

Modern Life and Physical Inactivity

Society has undergone dramatic changes in how people move throughout their daily lives. The shift towards less active jobs represents one of the most significant changes in physical activity patterns. The health risks of a sedentary lifestyle have increased as technology and automation replace physical labour.

The table below shows how dramatic workplace changes have affected physical activity levels over recent decades:

| Workplace Activity Changes Over Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Period | Workers in Active Jobs | Daily Movement at Work | Average Sitting Time |

| 1960s | Over 50% | Regular moderate-to-vigorous activity | 3-4 hours |

| Current Day | Less than 20% | Minimal movement required | Nearly 8 hours |

| Data shows the dramatic shift in workplace activity levels over the past 60 years | |||

This fundamental shift in daily movement patterns has created environments where the health risks of a sedentary lifestyle affect most working adults. The change goes beyond the workplace, affecting how children travel to school and how people spend their leisure time.

Young people face particular challenges in maintaining activity levels. The number of children walking or cycling to school has decreased significantly. In previous generations, active school transportation was a common practice. Today, longer school days combined with increased screen time have created unprecedented levels of inactivity among youth.

The average adult now spends close to eight hours of their waking time sitting, while engaging in less than 30 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity daily. This imbalance represents a dramatic departure from how humans have lived throughout history.

Reclaiming Your Active Life

Breaking free from inactive patterns requires understanding how movement affects health. Short breaks from sitting help reduce the adverse effects of prolonged inactivity. Even standing or taking brief walks provides benefits compared to continuous sitting.

Regular movement throughout the day helps maintain bone strength and muscle function. Research shows that consistent activity helps prevent rapid increases in bone breakdown during prolonged inactivity. The health risks of a sedentary lifestyle decrease when people find ways to move more frequently.

Different groups may need different approaches to increasing activity. Age, gender, and current fitness levels influence how people can best incorporate movement into their lives. The health risks of a sedentary lifestyle affect everyone differently, making personalised approaches important.

Physical activity does not require intense exercise to provide benefits. Simple movements like walking can improve health outcomes. Research shows that sudden cardiac events during physical activity are infrequent, occurring only once every 1.5 million episodes of vigorous activity.

Our bodies evolved to move regularly throughout the day. Modern life has created unprecedented levels of inactivity, but understanding these changes helps identify opportunities for movement. The evidence shows that regular physical activity remains essential for maintaining health and vitality in our increasingly sedentary world.

Sources

- Albert CM, Mittleman MA, Chae CU, Lee IM, Hennekens CH, Manson JE. Triggering of sudden death from cardiac causes by vigorous exertion. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(19):1355–61.

- Alfredsson L, Hammar N, Hogstedt C. Incidence of myocardial infarction and mortality from specific causes among bus drivers in Sweden. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22(1):57–61.

- Asghar A, Sheikh N. Role of immune cells in obesity induced low grade inflammation and insulin resistance. Cell Immunol. 2017 May;315:18-26.

- Bailey DP, Locke CD. Breaking up prolonged sitting with light-intensity walking improves postprandial glycemia, but breaking up sitting with standing does not. J Sci Med Sport. 2015; 18(3):294–8.

- Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJ, Martin BW. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? 2012;380(9838):258-71.

- Brown WJ, Bauman AE, Bull FC, Burton NW. Development of Evidence-Based Physical Activity Recommendations for Adults (18-64 Years) [Internet]: Canberra (Australia): Australian Government Department of Health; 2012.

- Caillot-Augusseau A, Lafage-Proust MH, Soler C, Pernod J, Dubois F, Alexandre C. Bone formation and resorption biological markers in cosmonauts during and after a 180-day space flight (Euromir 95). Clin Chem. 1998;44(3):578–85.

- Church TS, Thomas DM, Tudor-Locke C, et al. Trends over 5 decades in U.S. occupation-related physical activity and their associations with obesity. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19657.

- Dunstan DW, Barr EL, Healy GN, et al. Television viewing time and mortality: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Circulation. 2010;121(3):384–91.

- Ford ES, Caspersen CJ. Sedentary behaviour and cardiovascular disease: a review of prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(5):1338–53.

- Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1.6 million participants. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health Vol. 4 Iss. 1 (2019).

- Hather BM, Adams GR, Tesch PA, Dudley GA. Skeletal muscle responses to lower limb suspension in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1992;72(4):1493–8.

- Healy GN, Clark BK, Winkler EA, Gardiner PA, Brown WJ, Matthews CE. Measurement of adults’ sedentary time in population-based studies. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2):216–27.

- Inoue M, Tanaka H, Moriwake T, Oka M, Sekiguchi C, Seino Y. Altered biochemical markers of bone turnover in humans during 120 days of bed rest. Bone. 2000;26(3):281–6.

- Knight JA. Physical inactivity: associated diseases and disorders. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2012;42(3):320–37.

- Kohl HW III, Craig CL, Lambert EV, Inoue S, Alkandari JR, Leetongin G, Kahlmeier S; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):294–305.

- Lee I-M, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–29.

- Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360(9349):1903–13.

- McDonald NC. Active transportation to school: trends among U.S. schoolchildren, 1969–2001. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(6):509–16.

- Neufer PD. The effect of detraining and reduced training on the physiological adaptations to aerobic exercise training. Sports Med. 1989;8(5):302–20.

- Staron RS, Leonardi MJ, Karapondo DL, et al. Strength and skeletal muscle adaptations in heavy-resistance-trained women after detraining and retraining. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1991;70(2):631–40.

- Strain T, Flaxman S, Guthold R, Semenova E, Cowan M, Riley LM, Bull FC, Stevens GA; Country Data Author Group. National, regional, and global trends in insufficient physical activity among adults from 2000 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 507 population-based surveys with 5·7 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 2024 Aug;12(8):e1232-e1243.

- Tudor-Locke C, Brashear MM, Johnson WD, Katzmarzyk PT. Accelerometer profiles of physical activity and inactivity in normal weight, overweight, and obese U.S. men and women. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:60.

- van der Ploeg HP, Merom D, Corpuz G, Bauman AE. Trends in Australian children traveling to school 1971–2003: burning petrol or carbohydrates? Prev Med. 2008;46(1):60–2.

- Vukovich MD, Arciero PJ, Kohrt WM, Racette SB, Hansen PA, Holloszy JO. Changes in insulin action and GLUT-4 with 6 days of inactivity in endurance runners. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1996;80(1):240–4.

- Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, Davies MJ, Gorely T, Gray LJ, Khunti K, Yates T, Biddle SJ. Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2012;55(11):2895–905.

- World Health Organization. Physical Activity.

- World Health Organization. Physical Activity – Key Facts.