Sleep requirements change as humans develop, with distinct needs emerging at every life stage. Scientific research demonstrates how sleep patterns evolve dramatically, from spending almost all time in sleep-like states before birth to the refined sleep architecture of adulthood.

Current evidence reveals that children and teenagers require significantly more sleep than previous generations understood. Data from over 750,000 schoolchildren shows a concerning trend – young people now sleep two hours less per night than their counterparts from a century ago.

Sleep architecture undergoes remarkable transformations across the lifespan, characterised by shifts in timing, duration, and quality. These adaptations serve crucial developmental purposes, from brain maturation in infancy to emotional processing in adolescence. Additionally, sleep requirements change significantly between developmental phases.

Gender introduces another layer of complexity to sleep patterns. Scientific studies highlight how hormonal changes create unique sleep challenges for females during puberty, pregnancy, and menopause. Additionally, research shows women accumulate sleep debt more rapidly than men.

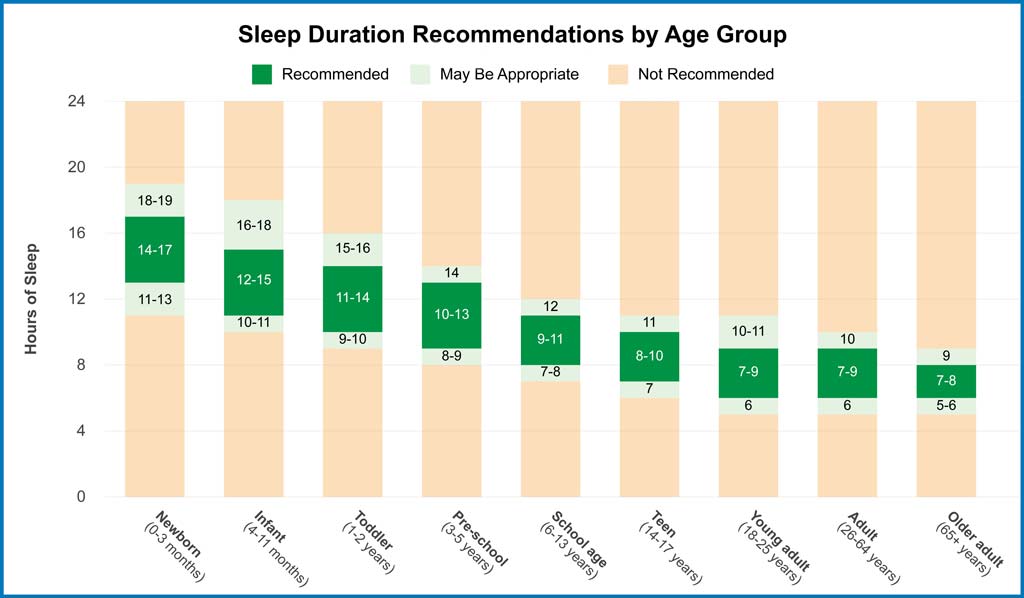

The visual guide below illustrates the recommended sleep durations across different age groups. These evidence-based guidelines reflect how sleep needs transition from the extensive requirements of newborns to older adults’ modified patterns.

From the precise coordination of sleep states in the developing foetus to the refined rhythms of maturity, the evolution of sleep reveals nature’s blueprint for human development. Through each stage, distinct patterns, challenges, and adaptations emerge that paint a compelling picture of how sleep supports growth, learning, and vitality.

Prenatal and Infant Sleep Development

Before birth, human foetuses spend most of their time in sleep-like states, with REM (rapid eye movement) sleep occupying nearly nine hours daily during the final two weeks of pregnancy. This early sleep period is not just a phase but a crucial stage for brain development, stimulating neural pathway growth and establishing crucial synaptic connections through synaptogenesis.

Newborns exhibit polyphasic sleep patterns (sleeping in multiple short periods rather than one long sleep), requiring 16 or more hours of sleep distributed across various periods throughout the day and night. Research shows that premature infants particularly benefit from controlled light exposure, with studies demonstrating that covered cribs during night hours accelerate growth and development while reducing hospital stays by 30%.

The circadian rhythm (the body’s natural 24-hour sleep-wake cycle) requires time to mature after birth, with newborns showing no signs of daily rhythm regulation until three to four months. Female infants display more advanced sleep patterns, demonstrating higher proportions of quiet sleep and extended sleep periods than male infants.

During the first six months, REM sleep comprises a higher percentage of total sleep than adults. Interestingly, children under age six typically do not report dream experiences despite having more REM sleep than adults, potentially due to underdeveloped cortical regions.

Micronutrient status significantly impacts early sleep development. Studies indicate iron deficiency anaemia in infancy causes lasting alterations in sleep architecture that persist into childhood, affecting both NREM (non-rapid eye movement) and REM sleep distribution.

Sleep Requirements Change During Childhood

Understanding the substantial changes in sleep requirements during childhood, with total sleep time shifting from 14-20 hours daily in infancy to approximately half before adolescence, is crucial. Research examining sleep patterns in children aged 5-7 shows that sleep consolidation typically occurs in a single sleep period, vital for their cognitive development.

Studies reveal significant individual variations in childhood sleep requirements, with confidence intervals showing a 10-hour range in sleep duration for young infants. Sleep architecture also transforms as children age, with REM sleep proportions increasing only during the first six months while slow-wave sleep remains enhanced until adolescence.

In preschool-aged children, sleep requirements change alongside cognitive development. Research demonstrates that decreases in napping correlate with higher vocabulary and enhanced memory during wake periods, indicating growth in memory-related brain regions. This highlights the cognitive benefits of adequate sleep in early childhood.

Examination of hippocampal (related to the hippocampus, a brain area key for memory) subfield volumes in children aged 4-6 years reveal differences between habitual and non-habitual nappers, even after controlling for variables like age, gender, and intracranial volume. These findings suggest that increasing memory storage efficiency in non-habitual nappers is a marker of brain maturation.

Environmental factors mainly influence children’s sleep patterns compared to adults. Studies show that youth in neighbourhoods with lower socioeconomic status exhibit poorer sleep health, including shorter nightly sleep durations.

Adolescent Sleep Transformation

During adolescence, sleep requirements change dramatically as the biological clock shifts, making teenagers naturally more alert at night and tired in the morning. This forward shift, ranging from 1 to 3 hours, is a significant biological change that affects their daily routines and should be understood.

Sleep duration during adolescence naturally decreases by approximately 1.5-3 hours between ages 15 and 18. During this period, melatonin (sleep hormone) production undergoes significant changes, with levels showing a dramatic decrease during puberty and a progressive decline after age 40-45.

REM sleep becomes particularly crucial during adolescence as adolescents navigate complex social and emotional situations. The brain heavily relies on REM sleep’s emotional calibration benefits during this critical developmental period. Deep NREM sleep is vital in brain maturation, helping prune and refine neural connections.

Adolescent athletes display unique sleep patterns, typically falling asleep earlier and waking earlier than non-athletic peers. However, research indicates that young athletes, particularly of Asian origin, demonstrate poor sleep efficiency (the percentage of time spent asleep while in bed) with extended wake periods after sleep onset.

Studies show females tend to wake earlier than males after puberty, a difference that disappears in middle age as sex hormones decline. Furthermore, chronotype (individual preference for morning or evening activity) typically shifts toward evening preference during adolescence before reverting to earlier patterns post-maturation.

Sleep Requirements Change in Adults

Sleep requirements change throughout adulthood, with most adults requiring 7-9 hours of sleep for optimal functioning. In the 30s and 40s, humans naturally revert to being early risers, finding it easier to fall asleep in the evening and wake at dawn.

The circadian rhythm regulation occurs through multiple pathways in adults. The SCN (Suprachiasmatic Nucleus) controls timing in peripheral organs through sympathetic pathways and hormonal signals like melatonin and glucocorticoids (stress hormones), providing temporal cues to tissues expressing their receptors.

Individual variations in sleep requirements change significantly between adults. Research indicates some people maintain good health with 5 hours of sleep while others need more than 9 hours to preserve daytime functioning. These differences appear linked to genetic factors, with studies showing specific clock gene polymorphisms (variations) affecting activity rhythms.

Gender differences persist in adult sleep patterns, with female sleep particularly affected by hormonal fluctuations. Progesterone levels influence sleep architecture, with elevated levels associated with reductions in REM sleep. Research demonstrates women’s heightened vulnerability to sleep disturbance effects, showing more significant increases in inflammatory markers.

Adults who maintain regular exercise routines experience better sleep quality. Studies show initiating moderate-intensity exercise programmes significantly improves sleep quality and autonomic (involuntary nervous system) status in previously sedentary individuals.

Age-Related Sleep Alterations

Sleep requirements change profoundly in older adults, who lose 80-90% of deep sleep compared to teenagers while maintaining similar overall sleep needs. Research indicates sleep architecture undergoes marked changes with ageing, characterised by reduced slow-wave sleep, decreased REM sleep, and increased sleep fragmentation.

Melatonin production significantly declines with age, often accompanied by pineal gland calcification. By age 70, melatonin levels represent only 10% of prepubertal levels, affecting sleep consolidation and maintenance. However, older individuals demonstrate notable resilience, showing less vulnerability to sleep loss effects on neurobehavioral performance than young adults.

Age-related changes in circadian organisation result in older adults awakening at an earlier internal phase than young adults. This earlier awakening leads to earlier light exposure that resets their circadian clock. Studies reveal that older adults require more light exposure to impact their sleep patterns, highlighting altered brain responsiveness to environmental cues.

Research using fruit flies demonstrates how ageing impacts sleep recovery mechanisms. While young flies compensated for sleep disruption by sleeping longer the next day, older flies failed to show this compensatory response. This suggests ageing brains may lose the ability to track sleep debt and implement recovery strategies.

Long-term studies indicate that sleep quality rather than duration becomes increasingly crucial with age. Research shows older adults often wake up after only 5 hours feeling refreshed. Yet, this reduced sleep duration may have health implications. Sleep requirements change to favour lighter sleep with increased sensitivity to environmental disruptions like sound and light.

The fascinating relationship between sleep and ageing reveals nature’s complex adaptations across the human lifespan. From the vigorous deep sleep of youth to the lighter patterns of advanced age, these changes reflect the brain’s extraordinary plasticity in responding to different life stages.

Sources

- Backhaus J, Hoeckesfeld R, Born J, et al. Immediate as well as delayed post learning sleep but not wakefulness enhances declarative memory consolidation in children. Neurobiol Learn Mem, 2008

- Baker FC, Lee KA. Menstrual cycle effects on sleep. Sleep Med Clin, 2018

- Blumberg, M.S., Seelke, A.M. The form and function of infant sleep: from muscle to neocortex. Oxford Handbook of Developmental Behavioral Neuroscience, 2010

- Butkov N. Atlas of clinical polysomnography. 2nd ed. Medford [Ore.]: Synapse Media, 2010

- Campbell IG, Van Dongen HPA, Gainer M, et al. Differential and interacting effects of age and sleep restriction on daytime sleepiness and vigilance in adolescence: a longitudinal study. Sleep, 2018

- Facer-Childs E, Brandstaetter R. The impact of circadian phenotype and time since awakening on diurnal performance in athletes. Curr Biol, 2015

- Galatius-Jensen S, Hansen J, Rasmussen V, et al. Nocturnal hypoxemia after myocardial infarction: association with nocturnal myocardial ischaemia and arrhythmias. Br Heart J, 1994

- Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s Sleep Time Duration Recommendations: Methodology and Results Summary. Sleep Health, 2015

- Iglowstein I, Jenni OG, Molinari L, Largo RH. Sleep duration From infancy to adolescence: Reference values and generational trends. Pediatrics, 2004

- Karan M, Bai S, Almeida DM, et al. Sleep-Wake Timings in Adolescence: Chronotype Development and Associations with Adjustment. J Youth Adolesc, 2021

- Kryger M, Roth T, Dement WC (2017). Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

- Lam JC, Mahone EM, Mason T, Scharf SM. The effects of napping on cognitive function in preschoolers. J Dev Behav Pediatr, 2011

- Luppi PH, Gervasoni D, Verret L, et al. Paradoxical (REM) sleep genesis: the switch from an aminergic-cholinergic to a GABAergic-glutamatergic hypothesis. J Physiol, 2006

- McCarley RW. Neurobiology of REM and NREM sleep. Sleep Med, 2007

- McLaughlin Crabtree V, Beal Korhonen J, Montgomery-Downs HE, et al. Cultural influences on the bedtime behaviors of young children. Sleep Med, 2005

- Monma T, Ando A, Asanuma T. Sleep disorder risk factors among student athletes. Sleep Med, 2018

- Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, et al. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep, 2004

- Peirano P, Algarín C, Garrido M et al. Iron-deficiency anemia is associated with altered characteristics of sleep spindles in NREM sleep in infancy. Neurochem Res, 2007

- Pevet P, Challet E. Melatonin: both master clock output and internal time-giver in the circadian clocks network. J Physiol, 2011

- Riggins T, Spencer RMC. Habitual sleep is associated with both source memory and hippocampal subfield volume during early childhood. Sci Rep

- Shaw PJ, Tononi G, Greenspan RJ, Robinson DF. Stress response genes protect against lethal effects of sleep deprivation in Drosophila. Nature, 2002

- Song Y, Blackwell T, Yaffe K, et al. Relationships between sleep stages and changes in cognitive function in older men: The MrOS Sleep Study. Sleep, 2015

- Tarokh L, Saletin JM, Carskadon MA. Sleep in Adolescence: Physiology, Cognition and Mental Health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2016

- Zhang J, Hobkirk J, Carroll S, et al. Exploring quality of life in patients with and without heart failure. Int J Cardiol, 2016

- Van Someren EJ, Riemersma RF, Swaab DF. Functional plasticity of the circadian timing system in old age: light exposure. Prog Brain Res, 2002

- Wheaton AG. Sleep Duration and Injury-Related Risk Behaviors Among High School Students—United States, 2007–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2016

- Whitney P, Hinson JM, Jackson ML, Van Dongen HPA. Feedback blunting: total sleep deprivation impairs decision making that requires updating based on feedback. Sleep, 2015

- Wright, C.J., Milosavljevic, S., Pocivavsek, A. The stress of losing sleep: sex-specific neurobiological outcomes. Neurobiol Stress, 2023

- Xie Z, Chen F, Li WA, et al. A review of sleep disorders and melatonin. Neurol Res, 2017