Physical activity trends worldwide reveal a concerning pattern—we’re moving less, not more, despite the fitness industry’s explosive growth. Strain and colleagues’ comprehensive study (2024) analysed data from 507 population-based surveys involving 5.7 million participants across 163 countries.

Their findings expose a startling reality: in 2022, nearly one-third of adults globally (31.3%) failed to meet recommended physical activity levels.

This global inactivity has worsened significantly since 2000, when the figure stood at 23.4%. In practical terms, approximately 1.8 billion adults worldwide aren’t getting enough movement for essential health maintenance.

The World Health Organization recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity weekly. Yet, this modest target remains unmet by a growing portion of the population.

The study highlights striking disparities across regions, ages, and genders. Some areas show improving activity levels, while others face dramatic declines. South Asia and high-income Asia Pacific regions have experienced the steepest increases in physical inactivity. Meanwhile, certain European countries and areas like Oceania demonstrate positive trends towards more active populations.

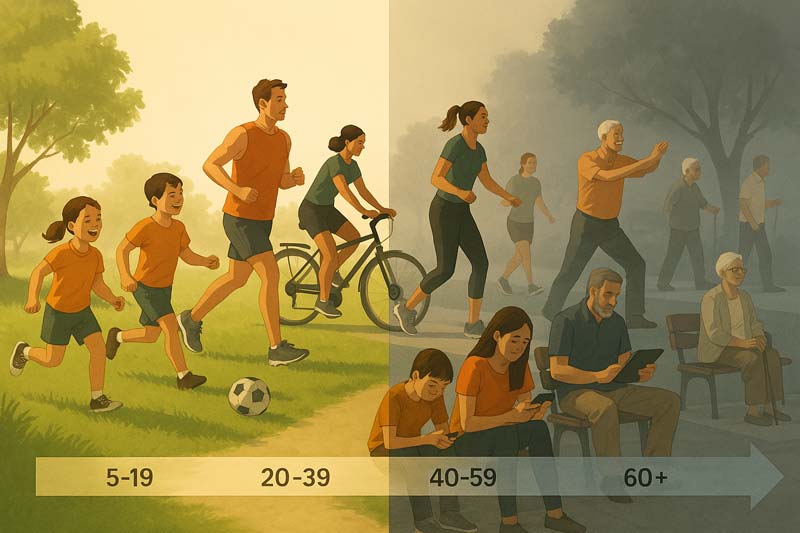

Age patterns reveal when people typically become less active – with sharp drops after age 60 across nearly all regions. However, the patterns differ markedly for younger adults based on geography and gender.

Perhaps most concerning is the persistent gender gap, with women’s physical inactivity rates averaging 5 percentage points higher than men’s globally – and reaching a 14-point difference in South Asia.

In this post, we dig deeper into these physical activity trends, examining how age affects movement patterns, persistent gender disparities in activity levels, regional variations that challenge our assumptions, and what these findings mean for everyday health. These insights tell a story about how modern life has shaped our relationship with physical activity and what we might do to reverse these concerning patterns.

The Paradox: Declining Physical Activity Trends in a Fitness-Obsessed World

We live in a world seemingly obsessed with fitness. Gym memberships have soared, fitness influencers dominate social media, and wearable technology tracks our every step. Yet despite this apparent fitness boom, the data tells a different story – globally, we’re becoming less active, not more.

The study reveals a troubling increase in insufficient physical activity worldwide. In 2000, about 23.4% of adults weren’t meeting minimum activity requirements. By 2022, this figure had jumped to 31.3% – representing an additional 900 million inactive adults. If current physical activity trends continue, projections suggest this number will reach 34.7% by 2030, falling far short of the World Health Assembly’s target of a 15% reduction.

This contradiction raises important questions. Why, when fitness has never been more visible in our culture, are actual activity levels declining? The answer lies partly in how modern life has evolved. Technological advances have eliminated movement from many daily tasks, and jobs have shifted from manual labour to sedentary desk work.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this trend, with working from home removing even the light activity associated with commuting and moving around offices. Leisure time increasingly involves screens rather than active pursuits.

The table below shows the stark contrast between the growing fitness industry and the declining activity levels worldwide.

| Indicator | 2000s | 2022 | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Physical Inactivity | 23.4% | 31.3% | ↑ 7.9% |

| Inactive Adults Worldwide | ~900 million | ~1.8 billion | ↑ 100% |

| Countries With Increasing Inactivity | – | 103 of 197 | 52% of countries |

| Regions With Increasing Inactivity | – | 6 of 9 | 67% of regions |

| Projected Inactivity (2030) | 26.4% (2010) | 34.7% | ↑ 8.3% from 2010 |

| WHO 2030 Target | 26.4% (2010) | 22.4% | ↓ 15% from 2010 |

The decline in physical activity isn’t evenly distributed across all parts of society. While gym attendance might rise among specific demographics, overall population activity levels are falling. This suggests that fitness culture may reach those predisposed to exercise while missing large population segments.

This trend is particularly worrying given the well-established link between physical activity and health. Regular activity reduces the risk of heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and certain cancers while improving mental health and cognitive function. We can expect corresponding increases in these health conditions as activity levels drop.

The physical activity trends in this study challenge us to look beyond fitness industry growth figures and examine what’s happening at a population level. They also suggest that current approaches to promoting physical activity may not work as effectively as we’d hoped.

New strategies may be needed to reverse these patterns and ensure movement becomes part of everyday life for all – not just those already engaged with fitness culture.

How Age Affects Our Movement Patterns

Age plays a crucial role in shaping our activity levels throughout life. The study reveals distinctive age-related physical activity trends that vary by region and gender. These patterns help identify when and why people tend to become less active.

Across nearly all regions, physical inactivity sharply increases after age 60. This age-related decline is consistent worldwide, with inactivity rates climbing steeply in the 60-69, 70-79, and 80+ age groups. For example, while global inactivity rates average 31.3% across all adults, this rises dramatically among older adults, often exceeding 50% in those over 80.

However, what happens before age 60 varies significantly by region and gender. The most common pattern for men globally shows a gentle increase in insufficient physical activity until approximately age 60, followed by a steeper rise.

Women’s patterns differ, often showing a J-shaped curve (where values initially decrease before rising again, resembling the letter J) where activity levels improve slightly during middle age before declining after 60.

Regional differences in physical activity trends are particularly striking. In East and Southeast Asia, men show stable or even decreasing inactivity levels up to age 60. At the same time, women demonstrate an apparent decrease in insufficient physical activity until this age. This contrasts sharply with high-income Asia Pacific countries, where inactivity increases steadily across all age groups for both genders.

These variations likely reflect cultural norms, life stages, and societal structures. Working-age adults may maintain higher activity levels in regions where physical labour remains common. Similarly, in areas where traditional gender roles persist, women’s activity patterns may align with changing domestic responsibilities throughout life.

The consistent drop in activity among older adults highlights a critical intervention point. With global populations ageing rapidly, addressing the activity needs of older adults becomes increasingly important. Exercise programmes tailored to older adults’ abilities and preferences could help maintain independence and quality of life.

Age-related activity patterns suggest that different approaches are needed for different life stages. Rather than applying one-size-fits-all approaches, activity promotion can address the specific barriers and motivators relevant to other age groups across various cultural contexts.

The Gender Gap: Why Women Move Less Than Men

One of the most persistent findings in the global analysis of physical activity trends is the gender gap. Worldwide, women consistently show higher rates of insufficient physical activity than men.

In 2022, the global prevalence of insufficient physical activity was 33.8% among women compared to 28.7% among men – a 5 percentage point difference.

This gender gap isn’t uniform across regions. South Asia shows the most dramatic disparity, with female inactivity rates (52.6%) a striking 14 percentage points higher than male rates (38.4%). In countries like Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, and several Caribbean nations, the female-male difference exceeds 20 percentage points.

These disparities highlight how cultural, social, and economic factors may create barriers to physical activity for women. The table below illustrates these regional gender differences in physical activity levels.

| Region | Male Inactivity | Female Inactivity | Gender Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global | 28.7% | 33.8% | +5.1% (women less active) |

| South Asia | 38.4% | 52.6% | +14.2% (women less active) |

| Central Asia & North Africa-Middle East | 32.8% | 44.2% | +11.4% (women less active) |

| Latin America & Caribbean | 31.9% | 41.2% | +9.3% (women less active) |

| High-income Western | 24.2% | 31.2% | +7.0% (women less active) |

| Central & Eastern Europe | 22.5% | 22.9% | +0.4% (nearly equal) |

| East & Southeast Asia | 26.9% | 22.2% | -4.7% (men less active) |

| China (specific country) | 28.0% | 19.5% | -8.5% (men less active) |

Interestingly, the pattern isn’t universal. In East and Southeast Asia, men show higher inactivity rates than women (26.9% vs. 22.2%). China exemplifies this reverse pattern, with an 8 percentage point difference favouring women. These exceptions to global physical activity trends suggest that cultural factors and gender roles profoundly influence activity patterns.

The reasons behind these gender disparities are multifaceted. In many societies, women face unique barriers to physical activity, including safety concerns, limited access to facilities, family responsibilities, and social norms that discourage female participation in sports. Women often bear a disproportionate share of domestic and caregiving duties, leaving less time for leisure-time physical activity.

Economic factors also play a role. Gender gaps in physical activity tend to be smaller in higher-income countries, suggesting that some barriers to women’s participation may diminish as countries develop economically.

However, the persistence of gender gaps even in wealthy nations indicates that economic development alone doesn’t eliminate all obstacles.

Addressing the gender gap in physical activity requires targeted approaches considering the barriers women face in different cultural contexts. Strategies might include creating safe spaces for women to be active, developing family-friendly activity programmes, challenging restrictive social norms, and ensuring equal access to resources and opportunities for physical activity across genders.

Regional Differences: Where Activity is Rising and Falling

The global picture of physical activity trends isn’t uniform – some regions are becoming increasingly inactive while others show positive trends. These regional variations provide valuable insights into what might drive changes in activity levels and what approaches might work to reverse negative trends.

South Asia has experienced the most dramatic increase in physical inactivity, rising from 22.4% in 2000 to 45.4% in 2022 – more than doubling in just over two decades. Similarly, high-income Asia Pacific countries have seen inactivity levels jump from 28.9% to 48.1% during this period. These regions represent the most concerning trends globally.

In stark contrast, some regions show encouraging improvements. Oceania’s inactivity rate has reduced from 22.5% in 2000 to 13.6% in 2022, while sub-Saharan Africa’s has decreased from 21.7% to 16.8%.

These positive trends suggest that physical activity decline isn’t inevitable – some regions have successfully fostered more active populations. The chart below shows how physical activity levels in different regions have changed over the past two decades.

REGIONAL CHANGES IN PHYSICAL ACTIVITY 2000-2022

| Region | 2000 | 2022 | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| South Asia | 22.4% | 45.4% | +23.0% |

| High-income Asia Pacific | 28.9% | 48.1% | +19.2% |

| Latin America & Caribbean | 28.6% | 36.6% | +8.0% |

| Central Asia & N.Africa-ME | 29.7% | 38.5% | +8.8% |

| Central & Eastern Europe | 15.4% | 22.7% | +7.3% |

| East & Southeast Asia | 19.0% | 24.6% | +5.6% |

| High-income Western | 31.6% | 27.7% | -3.9% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 21.7% | 16.8% | -4.9% |

| Oceania | 22.5% | 13.6% | -8.9% |

High-income Western countries present a somewhat mixed picture. While their overall inactivity rates remain high (27.7% in 2022), they’ve shown a modest improvement since 2000 (31.6%). Within this group, 12 Western European countries are on track to meet the global target of a 15% reduction in insufficient physical activity by 2030.

Income level appears to influence physical activity trends, but not in a straightforward way. Lower-middle-income countries have seen the steepest increases in inactivity (from 21.4% to 38.2%). In contrast, low-income countries have maintained relatively stable, lower levels of inactivity (around 17-19%).

This suggests rapid economic development might initially reduce physical activity as lifestyles change. At the same time, factors supporting activity may exist in very low—and high-income settings.

The success stories in regions like Oceania may be linked to policy efforts. The WHO Western Pacific region has implemented targeted actions to promote physical activity. Similarly, European countries showing positive trends have often adopted comprehensive, multi-sectoral policies addressing active transportation, recreation, and urban design.

These regional variations demonstrate that physical activity levels aren’t solely determined by individual choices but are shaped by broader social, economic, and policy environments. Success stories from regions bucking the global trend of increasing inactivity provide valuable lessons for addressing this challenge worldwide.

What These Physical Activity Trends Mean For Your Health

This global study’s declining physical activity trends significantly affect individual and public health. With nearly one-third of adults worldwide not meeting minimum activity recommendations, we face a growing health challenge that affects people of all ages and backgrounds.

Physical inactivity is linked to an increased risk of numerous health conditions. The WHO guidelines highlight how regular activity reduces the risk of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and several cancers. It also improves mental health, cognitive function, and sleep quality and helps maintain a healthy weight. As global inactivity rises, we can expect corresponding increases in these health conditions.

The message is clear for individuals – finding ways to incorporate movement into daily life has never been more important. The WHO recommendation of 150 minutes of moderate activity weekly might sound daunting, but this translates to just over 20 minutes daily.

Even small increases in activity can yield health benefits, especially for inactive people. The card set below summarises some key health benefits of regular physical activity.

The steady increase in inactivity with age highlights the importance of establishing activity habits that can be maintained throughout life. Finding sustainable forms of movement that match your interests and abilities is key to long-term adherence. This might mean different things at different life stages – from team sports in youth to walking groups or swimming in older age.

Women’s generally higher inactivity levels suggest a need for gender-sensitive approaches to activity promotion. Addressing barriers such as safety concerns, family responsibilities, and limited access to facilities could help close the gender gap and improve health outcomes for women globally.

Regional variations in physical activity trends offer both warning signs and hope. The rapid increases in inactivity in South Asia and high-income Asia Pacific regions signal the health challenges that can accompany specific development patterns. Meanwhile, success stories from Oceania and parts of Europe demonstrate that increasing activity levels is achievable with the right policies and cultural support.

The projected continuation of these trends to 2030 highlights the urgency of action. Without significant intervention, global inactivity levels will likely reach 34.7% by the end of the decade, leading to substantial preventable illness and premature death. Individual choices matter, but systemic changes to make physical activity easier, safer, and more accessible for all are equally important.

Sources

- Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:1451–1462.

- Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012;380:247–257.

- Mielke GI, da Silva ICM, Kolbe-Alexander TL, Brown WJ. Shifting the physical inactivity curve worldwide by closing the gender gap. Sports Med. 2018;48:481–489.

- Milton K, Varela AR, Strain T, Cavill N, Foster C, Mutrie N. A review of global surveillance on the muscle strengthening and balance elements of physical activity recommendations. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls. 2018;3:114–124.

- Sallis JF, Bull F, Guthold R, et al. Progress in physical activity over the Olympic quadrennium. Lancet. 2016;388:1325–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30581-5.

- Strain T, Flaxman S, Guthold R, Semenova E, Cowan M, Riley LM, Bull FC, Stevens GA; Country Data Author Group. National, regional, and global trends in insufficient physical activity among adults from 2000 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 507 population-based surveys with 5·7 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 2024 Aug;12(8)

- The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. WHO Step up! Tackling the burden of insufficient physical activity in Europe. 2023.

- WHO Assessing national capacity for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: report of the 2021 global survey. 2023.

- WHO Global status report on physical activity 2022. 2022.

- WHO More active people for a healthier world. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030. 2018.

- WHO Western Pacific Region Western Pacific Regional Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases (2014–2020) 2014.