By BeSund Editorial Team 11/07/2023 Modified Date: 07/10/2024

Osteoporosis and Bone Health

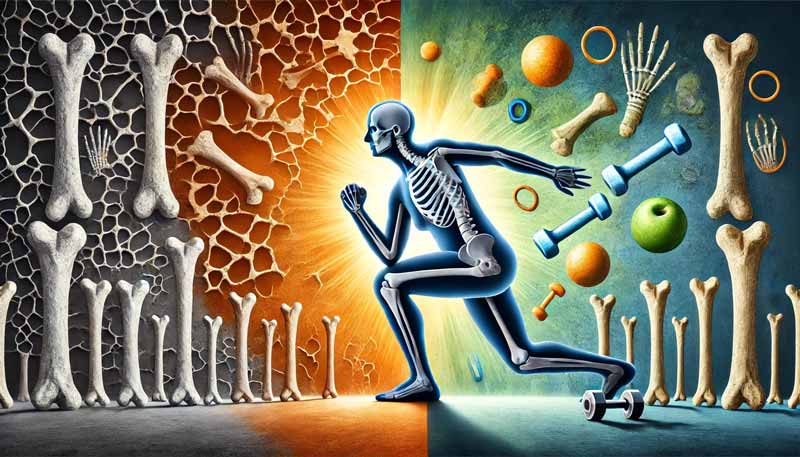

Learn about the role of exercise in bone health and osteoporosis

Osteoporosis and Bone Health

Understanding Osteoporosis and Bone Health

Osteoporosis and bone health are critical concerns affecting millions worldwide, with far-reaching impacts on quality of life and public health. This skeletal disorder, characterised by decreased bone mass and deterioration of bone tissue, significantly increases the risk of fractures. As our global population ages, the prevalence of osteoporosis continues to rise, making it a pressing health issue that demands attention. The consequences of osteoporosis go beyond the immediate risk of fractures. Osteoporosis encompasses a range of physical, emotional, and social challenges that can profoundly affect an individual’s independence and well-being. From chronic pain to reduced mobility, the ripple effects of this condition touch nearly every aspect of daily life. However, there is hope within these challenges. Research highlights the essential role of physical activity in maintaining bone health and preventing osteoporosis. This relationship between exercise and skeletal strength offers a promising avenue for controlling and managing the condition.

Understanding Osteoporosis: Definition and Prevalence

Osteoporosis, often called the ‘silent disease’, is a skeletal disorder characterised by compromised bone strength. This condition increases susceptibility to fractures, particularly in the hip, spine, and wrist. The term ‘osteoporosis’ literally means ‘porous bone’, reflecting bone tissue’s reduced density and quality. The global prevalence of osteoporosis is staggering, affecting approximately 18.3% of the population. Interestingly, there is a marked difference between genders, with women showing a higher prevalence (23.1%) than men (11.7%). As life expectancy increases worldwide, the incidence of osteoporosis and bone health issues is expected to rise. This trend poses significant challenges for healthcare systems and emphasises the importance of early prevention and management strategies.

The Impact of Osteoporosis and Bone Health on Quality of Life

Osteoporosis and bone health issues can profoundly affect an individual’s quality of life. The consequences of this condition involve intermediating against the risk of fractures and dealing with physical, emotional, and social dimensions. Fragility fractures, a hallmark of osteoporosis, can lead to severe pain, disability, and loss of independence. Hip fractures, in particular, carry a grim prognosis. Approximately one-third of individuals who experience a hip fracture die within 12 months, while 40% become institutionalised or lose their ability to walk independently. Moreover, the impact of osteoporosis on daily life can be substantial. Fear of falling may lead to reduced physical activity, social isolation, and decreased overall well-being. This cycle can further exacerbate bone loss and increase the risk of future fractures, creating a challenging situation for affected individuals.

Physical Activity and Its Role in Bone Health

Physical activity plays a crucial role in maintaining bone health throughout life. Regular exercise has been shown to promote bone mass increase, optimise bone geometry, and reduce bone mass loss and strength decline. These benefits are particularly significant in osteoporosis and bone health prevention and management. The relationship between mechanical stress and bone mass has been recognised since the late 17th century. This understanding has evolved into the modern concept of bone as a dynamic tissue capable of adapting to its mechanical environment. Weight-bearing and resistance exercises, in particular, have been shown to have optimal effects on bone mineral density and overall bone strength. Physical activity increases bone density and improves muscle strength, balance, and coordination, which is crucial for reducing the risk of falls and subsequent fractures.

The Impact of Osteoporosis on Physical Performance

Osteoporosis profoundly affects physical performance, creating a compound interaction between bone health and overall functional capacity. This skeletal condition increases fracture risk and influences muscle strength, balance, and endurance. With osteoporosis and bone health concerns, individuals often experience a cascade of physical challenges that can significantly alter their daily lives. From decreased mobility to reduced stamina, the implications of osteoporosis on physical performance are diverse and far-reaching.

Limitations on Physical Capabilities and Endurance

Individuals with osteoporosis and bone health issues often experience a decline in physical capabilities due to weakened bone structure. This deterioration can lead to reduced mobility, decreased muscle strength, and impaired balance, all contributing to a decline in overall physical performance. The impact on endurance and stamina is particularly noteworthy. Weakened bones can limit an individual’s ability to engage in prolonged physical activities, potentially leading to:

- Decreased cardiovascular fitness

- Reduced muscular endurance

- Lower overall physical activity levels

These limitations can create a cycle where reduced physical activity further exacerbates bone loss and muscle weakness, compounding the challenges faced by those with osteoporosis.

Specific Challenges in Physical Activities, Osteoporosis and Bone Health

Individuals with osteoporosis face unique obstacles during physical activities. The compromised bone strength can limit their ability to participate in high-impact exercises or activities that place excessive stress on the skeletal system. This limitation can significantly affect overall physical fitness and quality of life. Key challenges include:

- Increased risk of fractures during routine activities

- Fear of falling, leading to reduced physical activity

- Difficulty in maintaining proper posture and balance

- Limitations in performing weight-bearing exercises

The sad part of such limitations is that this results in a more sedentary lifestyle, which can further deteriorate bone health and physical performance.

The Impact of Osteoporosis on Muscle Strength and Power

Osteoporosis and bone health concerns affect bone health and significantly affect muscle strength and power. Research has shown that individuals with osteoporosis often exhibit preferential and diffuse type II muscle fibre atrophy, which is related to the degree of bone loss. This loss of muscle strength and power can have far-reaching effects:

- Increased risk of falls

- Reduced ability to perform daily activities

- Decreased overall functional capacity

Potential for further bone loss due to reduced physical activity

Exercise as a Management Tool for Osteoporosis and Bone Health

Exercise plays a crucial role in managing osteoporosis and bone health. It offers a comprehensive approach to improving bone density, strength, and overall physical performance. This non-pharmacological intervention provides multiple benefits that extend beyond just skeletal health. Impact on Bone Density Regular physical activity stimulates bone formation and adaptation. Weight-bearing exercises and resistance training have shown particular efficacy in maintaining and increasing bone mineral density (BMD). Studies indicate that high-intensity progressive resistance and impact weight-bearing training can significantly improve BMD, especially in the lumbar spine. Fracture Risk Reduction Exercise strengthens bones and also reduces the risk of falls, a major cause of fractures in individuals with osteoporosis and bone health issues. A meta-analysis found that exercise training reduced the risk of fall-related fractures by 40% in adults aged 50 years and over. Hormonal Regulation Physical activity influences the production and regulation of hormones crucial for bone metabolism. Regular exercise has been shown to promote the secretion of estrogen in premenopausal women and increase serum estradiol levels in postmenopausal women, partially mimicking the effects of hormone replacement therapy. Cytokine Balance Moderate exercise can positively impact the balance of cytokines involved in bone metabolism. Cytokine balance regulates molecules that promote or reduce inflammation, crucial for maintaining immune function and overall health. It increases levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines while decreasing pro-inflammatory ones, creating an environment favouring bone formation over resorption. Muscle Strength and Balance Exercise interventions for osteoporosis and bone health often lead to improvements in muscle strength, balance, and overall functional capacity. These enhancements significantly reduce fall risk and improve the quality of life for individuals with osteoporosis. While the effects of exercise on bone density may seem modest (typically a 1-3% increase), it’s important to note that even maintaining BMD can be clinically significant. This is particularly true given the average rate of bone loss in postmenopausal women, which can be as high as 2-4% per year in the first 5 to 10 years after menopause.

Recommended Exercises for Individuals with Osteoporosis

A well-structured exercise program can significantly improve bone density, reduce fracture risk, and enhance the overall quality of life for those with osteoporosis and bone health concerns. This section outlines evidence-based exercise recommendations tailored to individuals with osteoporosis, providing a comprehensive guide to safe and effective physical activity.

Multi-Modal Exercise Approach for Osteoporosis and Bone Health

A multi-modal exercise program is crucial for maximising the benefits of physical activity for individuals with osteoporosis and bone health concerns. This approach combines various types of exercises to address different aspects of bone health and overall fitness: Weight-Bearing Exercises:

- High-impact activities (for those without severe osteoporosis):

- Jumping

- Jogging

- Aerobics

- Low-impact activities:

- Brisk walking

- Stair climbing

- Low-impact aerobics

Resistance Training:

- Using free weights

- Weight machines

- Resistance bands

- Bodyweight exercises

Balance and Flexibility Exercises:

- Tai Chi

- Modified yoga

- Specific balance training exercises

Functional Exercises:

- Sit-to-stand movements

- Stepping exercises

- Functional reach activities

Each component of this multi-modal approach is vital in improving bone health and muscle strength and reducing fall risk.

FITT Recommendations for Osteoporosis Exercise Programs

The FITT principle (Frequency, Intensity, Time, and Type) provides a framework for structuring exercise programs for individuals with osteoporosis and bone health issues: Frequency:

- Weight-bearing exercises: 4-5 days per week

- Resistance training: 2-3 non-consecutive days per week

- Balance exercises: Daily

Intensity:

- Weight-bearing exercises: Moderate intensity (40%-59% of heart rate reserve)

- Resistance training: Start with 1 set of 8-12 repetitions, progressing to 2-3 sets

- Balance exercises: Challenging but safe

Time:

- Weight-bearing exercises: 30-60 minutes per session

- Resistance training: 20-30 minutes per session

- Balance exercises: 10-15 minutes per day

Type:

- Weight-bearing exercises: Walking, stair climbing, low-impact aerobics

- Resistance training: Exercises targeting major muscle groups

- Balance exercises: Static and dynamic balance activities, Tai Chi

These recommendations should be tailored to individual capabilities and gradually progressed over time.

Home-Based Low-Impact Exercise Program for Osteoporosis and Bone Health

A low-impact exercise program can be highly effective for those unable to access gym facilities or prefer home-based routines. Here’s a sample routine:

- Warm-up (5 minutes):

-

- Gentle whole-body movements

- Light stretching

- Core Program (20-30 minutes):

-

- Box step

- Heel presses

- Step-step-kick-step-step-back

- Upper body twists

- Cross steps

- Knee lift triangles

- Stomach exercise (shoulder lift off the floor)

- Rowing action

- Bent side leg raise

- Bent leg raise

- Front leg tucks

- Side leg presses

- Cool-down (5 minutes):

-

- Gentle stretching

- Pulse-lowering activities

This program should be performed at least twice weekly, gradually increasing intensity by adding repetitions or resistance.

Impact of Different Exercises on Bone Mineral Density

Understanding the specific effects of various exercises on bone mineral density (BMD) can help in designing targeted exercise programs:

- Swimming: Minimal impact on BMD, but beneficial for overall fitness

- Walking: Helps maintain BMD at the hip and lumbar spine

- Gentle aerobic exercise May increase BMD at the hip and lumbar spine

- Vigorous aerobic exercise: Increases BMD at the hip and lumbar spine

- Weight training: Increases BMD at hip, lumbar spine, and radius

- Running: Increases BMD at hip and lumbar spine

- Squash: Increases BMD at the hip, lumbar spine, and racquet hand

It is imperative to incorporate various exercises, especially weight-bearing and resistance training, for optimal osteoporosis and bone health. These evidence-based recommendations exercises, tailored to the individual needs and capabilities of those with osteoporosis, can significantly improve their bone health, reduce fracture risk, and enhance the overall quality of life.

Safety Measures and Precautions for Exercising with Osteoporosis

Safety should be paramount with osteoporosis and bone health concerns when engaging in physical activity. Proper precautions can significantly reduce the risk of fractures and other complications, allowing individuals to reap the benefits of exercise while minimising potential hazards. Key Safety Considerations:

- Consultation with Healthcare Professional:

- Seek advice before starting a new exercise programme

- Regular check-ups to monitor bone health and pain levels

- Adjust routines based on individual health status and bone density measurements

- Exercise Selection and Modification:

- Avoid high-impact activities and sudden twisting motions

- Focus on low-impact, weight-bearing exercises and controlled movements

- Modify exercises as needed, especially for those with severe osteoporosis or recent fractures

- Proper Form and Technique:

- Work with qualified fitness instructors or physical therapists

- Learn safe movement patterns, particularly for resistance training

- Maintain proper spinal alignment during all exercises

- Gradual Progression:

- Start with low-intensity exercises and shorter durations

- Follow the principle of progressive overload

- Increase intensity, frequency, or duration gradually under professional guidance

- Pain Monitoring:

- Differentiate between normal muscle soreness and potentially harmful pain

- Stop exercising if experiencing sharp or persistent pain

- Consult a healthcare professional about any new or worsening symptoms

Environmental and Equipment Safety:

- Ensure a safe exercise environment to prevent falls

- Use support objects during balance exercises

- Wear appropriate footwear with good traction

- Exercise indoors during inclement weather to reduce fall risk

Recognising that bone adaptation is gradual for individuals with osteoporosis and bone health issues is crucial. Exercise programmes should be sustained for at least 6 to 9 months, ideally 12 to 24 months, to observe significant changes in skeletal structure. Intensity Monitoring:

- Use heart rate monitors to gauge exercise intensity

- For moderate aerobic training, aim for 60% to 70% of reserve heart rate

- Calculate target heart rate: (220 – age – resting heart rate) * (60% to 70%) + resting heart rate

- Utilise the Borg scale to assess perceived exertion

Strength Training Precautions:

- Begin with bodyweight exercises and low-loads

- Focus on proper form before increasing intensity

- Avoid holding your breath during exertion

- Be cautious with exercises requiring forward bending or twisting

Special Considerations for High-Risk Individuals:

- Those with vertebral fractures or high fracture risk may need to avoid specific exercises

- Resistance training machines might require modification or avoidance

- Balance exercises should be performed near sturdy furniture or walls for support

Adhering to these safety measures and precautions, individuals with osteoporosis and bone health concerns can engage in beneficial exercise while minimising risks. Remember, the goal is to improve bone health and overall well-being through safe, consistent physical activity.

Living with Living with Osteoporosis and Bone Health: Fitness and Lifestyle Tips

Managing osteoporosis and bone health extends beyond exercise, encompassing a holistic approach to daily life. This section explores various aspects of living with osteoporosis and maintaining bone health, offering insights into nutrition, stress management, and long-term strategies. Nutritional Considerations:

- Calcium and Vitamin D: Essential for bone health

- Protein: Crucial for muscle strength and bone density

- Micronutrients: Zinc, copper, magnesium, and manganese play roles in bone metabolism

- Mediterranean Diet: Associated with enhanced muscle strength and functionality

Balanced nutrition supports overall health and complements physical activity in managing osteoporosis and bone health. Studies suggest combining exercise with calcium and vitamin D supplementation may synergistically affect bone health. Lifestyle Factors:

- Occupational Activity: Lifelong manual labour in men is associated with reduced rates of bone loss.

- Outdoor Activities: Regular walking (over 7.5 miles per week) correlates with increased bone mineral density.

- Smoking Cessation: Quitting smoking can help preserve bone density.

- Alcohol Moderation: Limiting alcohol consumption supports bone health.

- Stress Management: Chronic stress may negatively impact bone health through increased cortisol levels.

Stress Reduction Techniques:

- Meditation

- Deep breathing exercises

- Modified yoga practices

These practices support mental well-being and also contribute to better bone health management. Long-Term Management Strategies: Living with osteoporosis and maintaining bone health requires consistent, long-term commitment. Research indicates that individuals who previously maintained intensive exercise programmes could maintain their bone mineral density even after adopting less intensive routines for 5-7 years. Critical Components of Long-Term Management:

- Regular bone density scans

- Ongoing exercise adaptation

- Consistent nutritional support

- Fall prevention strategies

- Medication adherence (if prescribed)

Environmental Considerations: Creating a safe home environment is crucial for individuals living with osteoporosis and bone health concerns. This involves:

- Removing tripping hazards

- Ensuring adequate lighting

- Installing support structures in bathrooms

These measures significantly reduce fall risks, a critical aspect of fracture prevention in osteoporosis. Interestingly, research has shown the potential benefits of swimming for individuals with osteoporosis. While traditionally not considered a weight-bearing exercise, swimming may stimulate bone health through various mechanisms, including increased blood circulation and potential hormonal effects. It’s worth noting that osteoporosis management shares some similarities with arthritis management, particularly regarding the importance of regular physical activity and maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Both conditions benefit from tailored exercise programmes and nutritional support. Living with osteoporosis and maintaining bone health involves a multifaceted approach. Various factors contribute to overall bone health and quality of life, from nutrition and stress management to creating safe environments and engaging in appropriate physical activities.

Sources

- Ackerman K.E., Misra M. Bone Health and the Female Athlete Triad in Adolescent Athletes. Phys. Sportsmed. 2011;39:131–141.

- Beck B.R., Daly R.M., Singh M.A., Taaffe D.R. Exercise and Sports Science Australia (ESSA) position statement on exercise prescription for the prevention and management of osteoporosis. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20(5):438–445.

- Benedetti M.G., Furlini G., Zati A., Mauro L.G. The Effectiveness of Physical Exercise on Bone Density in Osteoporotic Patients. BioMed Res. Int. 2018;2018:4840531.

- Bentz A. T., Schneider C. M., Westerlind K. C. The relationship between physical activity and 2-hydroxyestrone, 16α-hydroxyestrone, and the 2/16 ratio in premenopausal women (United States) Cancer Causes & Control. 2005;16(4):455–461.

- Cawthon P.M., Fullman R.L., Marshall L. Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Research G Physical performance and risk of hip fractures in older men. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(7):1037–1044.

- Clarke B.L., Khosla S. Physiology of bone loss. Radiol Clin North Am. 2010;48(3):483–495.

- Cooper C., Atkinson E.J., Jacobsen S.J., O’Fallon W.M., Melton L., 3rd. Population-based study of survival after osteoporotic fractures. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137(9):1001–1005.

- Duckham R.L., Frank A.W., Johnston J.D., Olszynski W.P., Kontulainen S.A. Monitoring time interval for pQCT-derived bone outcomes in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(6):1917–1922.

- Edwards M.H., Dennison E.M., Sayer A.A., Fielding R., Cooper C. Osteoporosis and Sarcopenia in Older Age. Bone. 2015;80:126–130.

- El-Khoury F, Cassou B, Charles M-A, Dargent-Molina P. The effect of fall prevention exercise programmes on fall induced injuries in community-dwelling older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2013; 347.

- Giangregorio L.M., McGill S., Wark J.D. Too Fit To Fracture: outcomes of a Delphi consensus process on physical activity and exercise recommendations for adults with osteoporosis with or without vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(3):891–910.

- Gianoudis J., Bailey C.A., Ebeling P.R. Effects of a targeted multimodal exercise program incorporating high-speed power training on falls and fracture risk factors in older adults: a community-based randomised controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(1):182–191.

- Heinonen A, Oja P, Kannus P, et al. Bone mineral density in female athletes representing sports with different loading characteristics of the skeleton. Bone 1995;17:197–203.

- Kohrt W. M., Bloomfield S. A., Little K. D., Nelson M. E., Yingling V. R. Physical activity and bone health. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2004;36(11):1985–1996.

- Krall EA, Dawson-Hughes B. Walking is related to bone density and rates of bone loss. Am J Med 1994;96:20–6.

- McMillan L., Zengin A., Ebeling P., Scott D. Prescribing Physical Activity for the Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis in Older Adults. Healthcare. 2017;5:85.

- Nelson ME, Fiatarone MA, Morganti CM, et al. Effects of high-intensity strength training on multiple risk factors for osteoporotic fractures. A randomised controlled trial. JAMA 1994;272:1909–14.

- NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention Diagnosis and Therapy. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(6):785–795.

- Pietschmann P., Kudlacek S., Grisar J., et al. Bone turnover markers and sex hormones in men with idiopathic osteoporosis. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001;31(5):444–451.

- Pisani P., Renna M.D., Conversano F., Casciaro E., Di Paola M., Quarta E., Muratore M., Casciaro S. Major Osteoporotic Fragility Fractures: Risk Factor Updates and Societal Impact. World J. Orthop. 2016;7:171–181.

- Robinson RJ, Krzywicki T, Almond L, et al. Effect of a low-impact exercise program on bone mineral density in Crohn’s disease: a randomised controlled trial. Gastroenterology 1998;115:36–41.

- Salari N., Ghasemi H., Mohammadi L., Behzadi M.H., Rabieenia E., Shohaimi S., Mohammadi M. The Global Prevalence of Osteoporosis in the World: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021;16:609.

- Santos R. V. T., Viana V. A. R., Boscolo R. A., et al. Moderate exercise training modulates cytokine profile and sleep in elderly people. Cytokine. 2012;60(3):731–735.

- Terracciano C., Celi M., Lecce D. Differential features of muscle fiber atrophy in osteoporosis and osteoarthritis. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(3):1095–1100.

- Volpi E., Campbell W.W., Dwyer J.T., Johnson M.A., Jensen G.L., Morley J.E., Wolfe R.R. Is the Optimal Level of Protein Intake for Older Adults Greater than the Recommended Dietary Allowance? Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013;68:677–681.

- Watson S.L., Weeks B.K., Weis L.J., Harding A.T., Horan S.A., Beck B.R. High-Intensity Resistance and Impact Training Improves Bone Mineral Density and Physical Function in Postmenopausal Women With Osteopenia and Osteoporosis: The LIFTMOR Randomized Controlled Trial: Heavy lifting improves bmd in osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2018;33:211–220.

- Wiswell RA, Hawkins SA, Dreyer HC, et al. Maintenance of BMD in older male runners is independent of changes in training volume or VO(2)peak. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002;57:M203–8.

- Zhao R., Feng F., Wang X. Exercise interventions and prevention of fall-related fractures in older people: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):149–161.